In 2012, Viktor Klang published a tiny Java snippet that implemented a tiny actor system in about

about 20 lines of code; a few years later, a revised version showed how to do the same in Scala.

I think untyped actors in the style of Akka Classic have always felt clunky in Java; Java used to lack a way to express pattern matching concisely. However, a few days ago I realized that Java 17 provides enough syntactic sugar to write shorter actors:

- messages can be concisely written using Java records

- the behavior of an actor can now leverage pattern matching and switch expressions!

- as a bonus, the Java version of the snippet can be further simplified

In the following I will explain what an actor system is, I will show you how to implement the behavior of an actor using pattern matching and records, and finally, how to write the actor runtime using Java 17.

This blog post is part of a series. Next time, I will post a larger use case (a tiny chat client-server). In the third part, I will described a typed extension to this actor runtime.

Because this post is a bit long, I added here a table of contents.

And before we start, here is the full listing to whet your appetite. You can also find it at this repository:

package io.github.evacchi;

import java.util.concurrent.*;

import java.util.concurrent.atomic.AtomicInteger;

import java.util.function.Function;

import static java.lang.System.out;

public interface Actor {

interface Behavior extends Function<Object, Effect> {}

interface Effect extends Function<Behavior, Behavior> {}

interface Address { Address tell(Object msg); }

static Effect Become(Behavior like) { return old -> like; }

static Effect Stay = old -> old;

static Effect Die = Become(msg -> { out.println("Dropping msg [" + msg + "] due to severe case of death."); return Stay; });

record System(ExecutorService executorService) {

public Address actorOf(Function<Address, Behavior> initial) {

abstract class AtomicRunnableAddress implements Address, Runnable

{ final AtomicInteger on = new AtomicInteger(0); }

var addr = new AtomicRunnableAddress() {

final ConcurrentLinkedQueue<Object> mb = new ConcurrentLinkedQueue<>();

Behavior behavior = m -> (m instanceof Address self) ? Become(initial.apply(self)) : Stay;

public Address tell(Object msg) { mb.offer(msg); async(); return this; }

public void run() {

try { if (on.get() == 1) { var m = mb.poll(); if (m!=null) { behavior = behavior.apply(m).apply(behavior); } }}

finally { on.set(0); async(); }}

void async() {

if (!mb.isEmpty() && on.compareAndSet(0, 1)) {

try { executorService.execute(this); }

catch (Throwable t) { on.set(0); throw t; }}}

};

return addr.tell(addr);

}

}

}

{: style=“font-size: small”}

We will go through each line and learn what it is doing, and try the code along the way with the help of some examples. But first, let us set up our development environment.

JEP-330 and JBang 🔗

In order to make this more interactive, I will share each example as a stand-alone Gist.

JEP 330 has introduced a simple mechanism to evaluate single-file Java sources. This means that you can download each Gist with curl and then evaluate them with java

For instance, you can run this Hello World by downloading the raw contents and then running Hello.java through java.

curl -LO https://gist.githubusercontent.com/evacchi/a796c5bedb308249844ebf0f85392e92/raw/bc0be725a1ae68ba7ad3701755bfdd485cd2fd7b/Hello.java

java Hello.java

This is even easier if you have installed JBang. JBang makes it possible to run self-contained Java-based scripts quickly. You can even run a gist directly, like so:

j! https://gist.github.com/evacchi/a796c5bedb308249844ebf0f85392e92

Regardless if you used plain java or j! the output should read:

Hey, that was easy!

Now, JEP-330 only runs single-source files. You will be able to run all the following examples by pasting the code in the same source file as the min-java-actors source code and then run them through java.

But, with JBang, you will be able to point it to the Gist, and it will take care of all the rest, including downloading JDK 17, if you don’t have it installed! That’s nifty!

A Bit of Boilerplate 🔗

You may have noticed that our tiny actor runtime is all defined within an Actor interface:

public interface Actor {

This may look like a bizarre choice: why not class ?

As you know, a Java public type declaration (i.e. class, record enum or interface)

must be usually declared in its own separate file.

If you declare your types as package-private (i.e. you don’t specify an explicit visibility modifier) then you can write as many as you want in the same compilation unit. For instance:

// SomeName.java

class A {}

class B {}

interface C {}

The downside is that you cannot declare top-level static fields. Fields must always belong to a container. And besides… they are not public, which may or may not be what you want.

The usual trick is to nest type declarations into the body of another

type declaration, usually a class, and declare the nested items

as public; this of course allows you to have fields:

public class Actor {

public static class B {}

public final static String Foo = "";

}

You will have to write static in most cases: a non-static class captures the outer container

which in our case will not be what we want. So this is still quite verbose.

A lesser-known fact is that interface definitions allow public members

other than instance methods; the defaults for such members are different than those for classes

and they allow you to omit a lot of keywords:

- every field in an interface is

publicstaticfinal, - every

class,interface,recordorenumispublicstatic - every

staticmethod is alsopublic

Thus you can write:

public interface Actor {

class B {} // this is public static

static void f(); // this is public static

String Foo = ""; // this is public static final

}

In the following, we will assume that all the code is nested in public interface Actor {}

The Actor Model 🔗

I am going to lift the definition from Wikipedia:

An actor is a computational entity that, in response to a message it receives, can concurrently:

- send a finite number of messages to other actors;

- create a finite number of new actors;

- designate the behavior to be used for the next message it receives.

Behaviors and Effects 🔗

Implementation-wise, the behavior of an actor is a function that consumes a message and returns the “next”. In the body of this function, the actor usually sends messages to the addresses of other actors. It can also choose to spawn new actors.

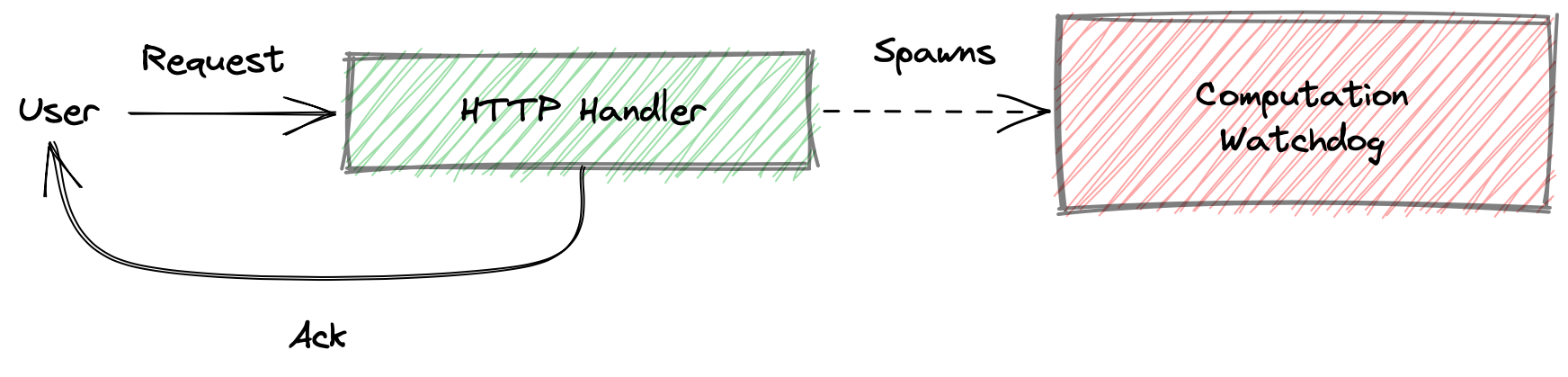

For instance, consider the case of an HTTP request to initiate a long computation. You may have an actor that receives a message and acknowledges the sender; then it may create the actor to process the request. The long computation will start and run asynchronously in the background, while the response will float back to the sender.

At its core, an actor is just a routine with a message queue. Instead of being evaluated synchronously, the routine is “posted” a message. The message stays in such a message queue (called sometimes a mailbox), until the actor is woken up by the runtime. When the actor is awake, then the runtime picks a message from the top of the mailbox and dispatches it to the routine (i.e. it invokes that routine with that message).

The routine is always of the form:

Function<Object, Effect> // Behavior

In other words, the Behavior of an actor is to receive a message of some type

and then return an Effect. We can send any type of object so we just use

Object. An Effect would be a way to describe a transition between two

states of the actor.

It can be represented as a function that takes the current Behavior and

returns the next Behavior:

Function<Behavior, Behavior> {}

We can name the Behavior and Effect functions by “aliasing” them:

interface Behavior extends Function<Object, Effect> {}

interface Effect extends Function<Behavior, Behavior> {}

Extending a class to rename it is pretty typical in a Java context.

Other languages, such as Scala provides facilities to give a synonym

to a type, an “alias” (typedef if you like C).

Even though extending an interface, in general, is not the same as aliasing, in the case of functional interfaces, it is kind of close, because you can always convert between different types if the signatures match (it is a form of “structural” typing if you will.)

Function<Object, Effect> f = x -> ...; // not a Behavior

Behavior = f::apply; // ooh, that's a Behavior!

In fact, you could also define Behavior explicitly:

interface Behavior {

Effect receive(Object message);

}

The most basic Effects (state transitions) are Stay and Die:

Staymeans no behavioral changeDiewill effectively turn off the actor, making it inactive.

For instance, this is a valid behavior for an actor that starts, then waits for one message, then it dies: i.e., it will drop and ignore all subsequent messages and/or the system may decide to collect it and throw it away.

Effect receiveThenDie(msg) {

out.println("Got msg " + msg);

return Actor.Die;

}

or written differently:

Behavior receiveThenDie = (msg) -> {

out.println("Got msg " + msg);

return Actor.Die;

};

One last final note on the definition of Behavior.

We could be more specific and always expect a message of a particular subtype, e.g:

interface Message {}

interface Behavior {

Effect receive(Message message);

}

But we will keep it simple for now.

Example 1: A Hello World 🔗

You can run the following example with:

j! https://gist.github.com/evacchi/40b19b0e116f3ce8f635787e0be79c95

In this example we will create an actor system,

then spawn an actor that will process one message and then Die.

You will recognize the behavior receiveThenDie that we defined above.

// create an actor runtime (an actor "system")

Actor.System actorSystem = new Actor.System(Executors.newCachedThreadPool());

// create an actor

Address actor = actorSystem.actorOf(self -> msg -> {

out.println("self: " + self + " got msg " + msg);

return Actor.Die;

});

The actorOf method returns an Address which is defined as follows:

interface Address { Address tell(Object msg); }

allowing us to write:

actor.tell("foo");

actor.tell("bar");

or just:

actor.tell("foo").tell("bar");

which, when executed, prints the following:

self: io.github.evacchi.Actor$System$1@198a98aa got msg foo

Dropping msg [bar] due to severe case of death.

because the "bar" message was sent to a dead actor.

If we change the lambda to return stay instead:

var actor = actorSystem.actorOf(self -> msg -> {

out.println("self: " + self + " got msg " + msg);

return Actor.Stay;

});

then the output would read:

self: io.github.evacchi.Actor$System$1@146b69a3 got msg foo

self: io.github.evacchi.Actor$System$1@146b69a3 got msg bar

Stay can be defined as such:

static Effect Stay = current -> current;

that is, a transition from the current behavior to the current behavior (i.e. it stays in the same state.)

Die is defined as:

static Effect Die = Become(msg -> {

out.println("Dropping msg [" + msg + "] due to severe case of death.");

return Stay;

});

where Become is:

static Effect Become(Behavior next) { return current -> next; }

i.e. Become is a method (despite the odd casing, for consistency with Stay and Die), that,

given a Behavior returns an effect. And that effect is taking the current behavior

and returning the next one.

Thus, Die is just an effect that takes the prev behavior and returns the behavior to drop

all messages, and then Stays in that state.

You may also be wondering about that little self up there.

self is a self-reference to the actor. It serves the same purpose as this in a class.

Because the behavior is written as a function, we need to “seed” a reference to

this into the function. But there is no this until

the actor is actually created by the runtime, so

we provide it in the closure, so that it may be filled lazily.

If this is not too clear, don’t worry for now; we’ll get to that later.

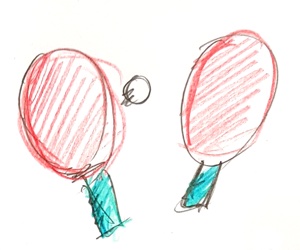

Example 2: Ping Pong 🔗

You can run the following example with:

j! https://gist.github.com/evacchi/97909cd131b8c358341b51463a40da04

In the previous example, the actor was consuming messages of any type (Object).

Let us now make it more interesting, and only accept some types.

This is where pattern matching and records come in handy.

An actor routine usually matches a pattern against the incoming message.

In Java versions before 17, switch expression and pattern matching

support was experimental; in general, they are very recent additions

(JEP-305 and JEP-361 both delivered in JDK 14).

In a classic example actor example, one actor sends a “ping” to another; the second replies with a “pong”, and they go on back and forth.

In order to make this more interesting (and also not to loop indefinitely):

- one of the actors (the

ponger) will receivePingand reply withPong; - it will also count 10

Pings, thenDie; - upon reaching 10 and before it

Dies, thepingerwill also send a message (DeadlyPong) to theponger - the

pingerreceivesPingand replies withPong - when it receives a

DeadlyPongitDies.

First, we define the Ping, Pong messages, with the Address of the sender.

record Ping(Address sender) {}

record Pong(Address sender) {}

We also define the DeadlyPong variant for Pong. This will be sent to the ponger

when the pinger is about to shut off.

record DeadlyPong(Address sender) {}

void run() {

var actorSystem = new Actor.System(Executors.newCachedThreadPool());

var ponger = actorSystem.actorOf(self -> msg -> pongerBehavior(self, msg, 0));

var pinger = actorSystem.actorOf(self -> msg -> pingerBehavior(self, msg));

ponger.tell(new Ping(pinger));

}

Effect pongerBehavior(Address self, Object msg, int counter) {

return switch (msg) {

case Ping p && counter < 10 -> {

out.println("ping! 👉");

p.sender().tell(new Pong(self));

yield Become(m -> pongerBehavior(self, m, counter + 1));

}

case Ping p -> {

out.println("ping! 💀");

p.sender().tell(new DeadlyPong(self));

yield Die;

}

default -> Stay;

};

}

Effect pingerBehavior(Address self, Object msg) {

return switch (msg) {

case Pong p -> {

out.println("pong! 👈");

p.sender().tell(new Ping(self));

yield Stay;

}

case DeadlyPong p -> {

out.println("pong! 😵");

p.sender().tell(new Ping(self));

yield Die;

}

default -> Stay;

};

}

The prints the following:

ping! 👉

pong! 👈

ping! 👉

pong! 👈

ping! 👉

pong! 👈

ping! 👉

pong! 👈

ping! 👉

pong! 👈

ping! 👉

pong! 👈

ping! 👉

pong! 👈

ping! 👉

pong! 👈

ping! 👉

pong! 👈

ping! 👉

pong! 👈

ping! 💀

pong! 😵

Dropping msg [Ping[sender=io.github.evacchi.Actor$System$1@3b9c1475]] due to severe case of death.

the line:

case Ping p && counter < 10 -> {

is a “guarded pattern”, that is, a pattern with a guard (a boolean expression). The expression may be

on any variable or field that is in scope including the matched value (p in this case). This is still

a preview feature, so it requires the --enable-preview flag.

Ignored Messages 🔗

You may have noticed that all our switches have a default case. This is because

any type of message is allowed; in fact, recall the Address interface and the signature of tell():

interface Address { Address tell(Object msg); }

If we send an object of a type that is not handled, it will just be silently swallowed:

ponger.tell("Hey hello"); // prints nothing

In order to keep these examples simple we just ignored the message;

you may want to add some logging to the default case, instead:

return switch (msg) {

case ...

default -> {

out.println("Ignoring unknown message: " + msg);

yield Stay;

}

};

Closures vs Classes 🔗

Notice how the traditional way to increase a counter is to create a closure with the value:

void run() {

...

var ponger = actorSystem.actorOf(self -> msg -> pongerBehavior(self, msg, 0));

...

}

Effect pongerBehavior(Address self, Object msg, int counter) {

return switch (msg) {

case Ping p && counter < 10 -> {

...

yield Become(m -> pongerBehavior(self, m, counter + 1));

}

...

}

}

However, a similar effect could be achieved with mutable state; this is perfectly acceptable, because the state of an actor is guaranteed to execute in a thread-safe environment. In this case we could have written:

void run() {

...

var ponger = actorSystem.actorOf(StatefulPonger::new);

...

}

class StatefulPonger implements Behavior {

Address self; int counter = 0;

StatefulPonger(Address self) { this.self = self; }

public Effect apply(Object msg) {

return switch (msg) {

case Ping p && counter < 10 -> {

out.println("ping! 👉");

p.sender().tell(new Pong(self));

this.counter++;

yield Stay;

}

case Ping p -> {

out.println("ping! 💀");

p.sender().tell(new DeadlyPong(self));

yield Die;

}

default -> Stay;

};

}

}

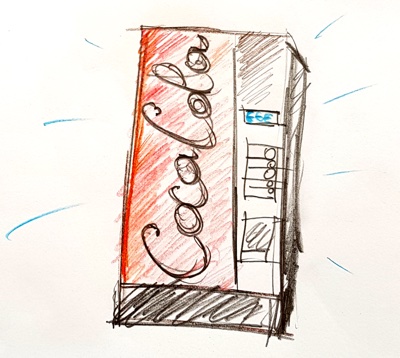

Example 3: A Vending Machine 🔗

You can run the following example with:

j! https://gist.github.com/evacchi/a46827cdcbdfefd93cf003459bb6fee1

In the previous example, we saw how we can use actors to maintain mutable state.

But we also saw that when an actor receives a message it returns an Effect; that is, a transition

to a different behavior. So far we only only used two built-in effects: Stay and Die.

But we can use the Become mechanism to change the behavior of our actors upon receiving a message. In other words, actors can be used to implement state machines.

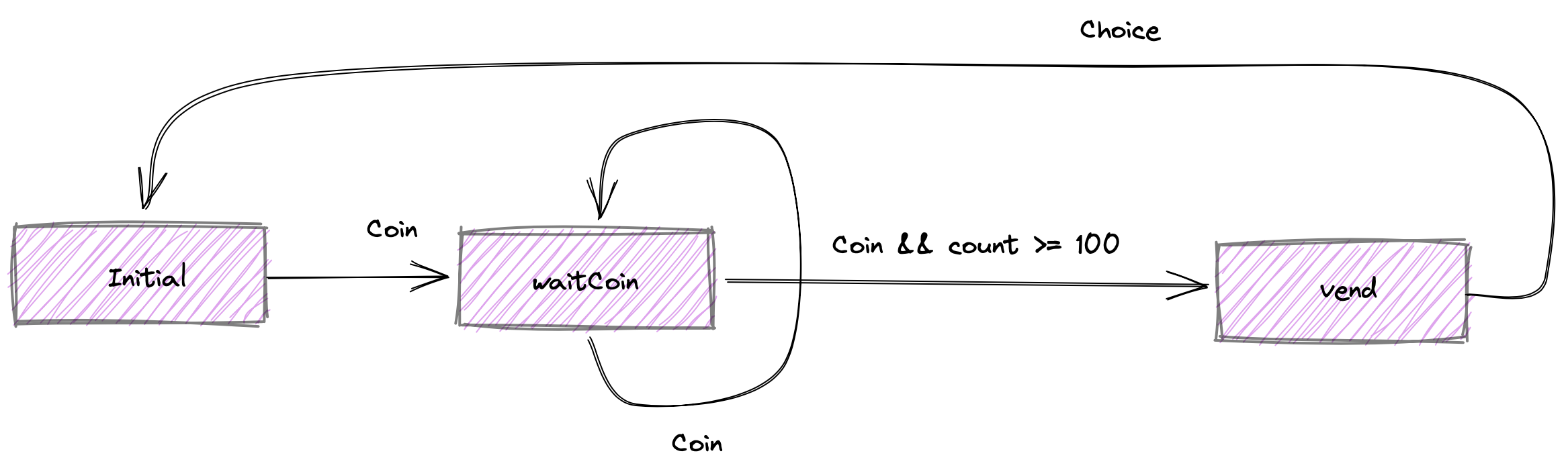

A classic example of a state machine is the vending machine: a vending machine awaits for a specific amount of coins before it allows to pick a choice. Let us implement a simple vending machine using our actor runtime.

Suppose that you are developing a vending machine that waits for you to insert an amount of 100 before you can pick a choice. Then you can pick your choice and your item will be retrieved. For simplicity, we assume that each coin has a value between 1 and 100.

The messages will be:

record Coin(int amount){

public Coin {

if (amount < 1 && amount > 100)

throw new AssertionError("1 <= amount < 100"); }

}

record Choice(String product){}

And the behavior will be:

Effect initial(Object message) {

return switch(message) {

case Coin c -> {

out.println("Received first coin: " + c.amount);

yield Become(m -> waitCoin(m, c.amount()));

}

default -> Stay; // ignore message, stay in this state

};

}

Effect waitCoin(Object message, int counter) {

return switch(message) {

case Coin c && counter + c.amount() < 100 -> {

var count = counter + c.amount();

out.println("Received coin: " + count + " of 100");

yield Become(m -> waitCoin(m, count));

}

case Coin c -> {

var count = counter + c.amount();

out.println("Received last coin: " + count + " of 100");

var change = counter + c.amount() - 100;

yield Become(m -> vend(m, change));

}

default -> Stay; // ignore message, stay in this state

};

}

Effect vend(Object message, int change) {

return switch(message) {

case Choice c -> {

vendProduct(c.product());

releaseChange(change);

yield Become(this::initial);

}

default -> Stay; // ignore message, stay in this state

};

}

void vendProduct(String product) {

out.println("VENDING: " + product);

}

void releaseChange(int change) {

out.println("CHANGE: " + change);

}

This actor may be created by an actor system by passing the initial state:

var actorSystem = new Actor.System(Executors.newCachedThreadPool());

var vendingMachine = actorSystem.actorOf(self -> msg -> initial(msg));

and then started with:

vendingMachine.tell(new Coin(50))

.tell(new Coin(40))

.tell(new Coin(30))

.tell(new Choice("Chocolate"));

It will print the following:

Received first coin: 50

Received coin: 90 of 100

Received last coin: 120 of 100

VENDING: Chocolate

CHANGE: 20

If an action is costly (e.g. blocking), an actor may decide to spawn another actor to serve that action. For instance:

record VendItem(String product){}

record ReleaseChange(int amount){}

Effect vend(Object message, int change) {

return switch(message) {

case Choice c -> {

var vendActor = system.actorOf(self -> m -> vendProduct(m));

vendActor.tell(new VendItem(c.product()))

var releaseActor = system.actorOf(self -> m -> release(m));

releaseActor.tell(new ReleaseChange(change))

yield Become(this::initial);

}

default -> Stay; // ignore message, stay in this state

...

}

}

Effect vendItem(Object message) {

return switch (message) {

case VendItem item -> {

// ... vend the item ...

yield Die // we no longer need to stay alive.

}

}

}

Effect release(Object message, int change) {

return switch (message) {

case ReleaseChange c -> {

// ... release the amount ...

yield Die // we no longer need to stay alive.

}

}

}

Implementing The Actor System 🔗

We are now ready to implement the actor system and execution environment.

The original Scala snippet does away with an ActorSystem object, because it leverages

the implicit feature to inject an Executor automatically:

implicit val e: java.util.concurrent.Executor = java.util.concurrent.Executors.newCachedThreadPool

// implicitly takes e as an Executor

val actor = Actor( self => msg => { println("self: " + self + " got msg " + msg); Die } )

Although that is convenient we can achieve just the same result by creating a factory object

(Actor.System) carrying the ExecutorService for us. The method Actor#apply is defined in Scala as follows:

def apply(initial: Address => Behavior)(implicit e: Executor): Address

that allows to create an actor with Actor( self => msg => ... ); can be substituted by a method

actorOf of the Actor.System factory.

public interface Actor {

class System {

Executor executor;

public System(Executor executor) { this.executor = executor; }

public Address actorOf(Function<Address, Behavior> initial) {

// ... references the executor ...

}

}

}

However, in order to keep the number of lines down, we can abuse the record construct so that we

don’t have to write an explicit constructor:

record System(Executor executor) {

public Address actorOf(Function<Address, Behavior> initial) {

// ... references the executor ...

}

}

The original Scala code defines a private abstract class AtomicRunnableAddress .

We picked interface Actor as the outer container. However interfaces (currently) do not allow

private class members. But the purpose of AtomicRunnableAddress is really to create an

anonymous class that implements two interfaces in the body of the apply() method:

private abstract class AtomicRunnableAddress extends Address with Runnable { val on = new AtomicInteger(0) }

def apply(initial: Address => Behavior)(implicit e: Executor): Address =

new AtomicRunnableAddress { // Memory visibility of "behavior" is guarded by "on" using volatile piggybacking

We can use another under-used feature of Java: local classes; i.e. a class that is local to the body of a method. So instead of:

abstract class AtomicRunnableAddress implements Address, Runnable

{ AtomicInteger on = new AtomicInteger(0); }

record System(ExecutorService executorService) {

public Address actorOf(Function<Address, Behavior> initial) {

we write:

record System(ExecutorService executorService) {

// Seeded by the self-reference that yields the initial behavior

public Address actorOf(Function<Address, Behavior> initial) {

abstract class AtomicRunnableAddress implements Address, Runnable

{ AtomicInteger on = new AtomicInteger(0); }

which makes AtomicRunnableAddress private to that method (which is all we need).

We will use the AtomicInteger to turn on and off the actor (note: we could probably use an AtomicBoolean, but

we are just following the original code).

we now create our object:

var addr = new AtomicRunnableAddress() {

// the mailbox is just concurrent queue

final ConcurrentLinkedQueue<Object> mbox = new ConcurrentLinkedQueue<>();

// current behavior is a mutable field.

Behavior behavior =

// the initial behavior is to receive an address and then apply the initial behavior

m -> { if (m instanceof Address self) return new Become(initial.apply(self)); else return Stay; };

...

};

addr.tell(addr);

Here is the reason why our actors are created with this strange curried function:

var actor = system.actorOf(self -> msg -> ...);

the signature for the initial behavior is really: Function<Address, Behavior> which “expands” to

Function<Address, Function<Object, Effect>>

or, to write it in a possibly more readable format:

Address -> Object -> Effect

// self -> msg -> ...

The reason why we write it this way is so that the Function<Object, Effect> (i.e. the Behavior)

can reference self. As we saw in Example 3: A Vending Machine this is often equivalent to writing a class

that takes an Address in its constructor. And that is because “a closure is a poor man’s object; an object is a poor man’s closure”.

When the actor starts we send the address to itself:

addr.tell(addr);

Let us now take a look at the tell() method; at its core we may write it as:

public void tell(Object msg) {

// put message in the mailbox

mb.offer(msg);

async();

}

The async method verifies that the mbox contains an element and schedules the actor

for execution on the Executor.

void async() {

// if the mbox is non-empty and the actor is active

if (!mb.isEmpty() && on.getAndSet(1) == 0)) {

// schedule to run on the Executor

try { executor.execute(this); }

// in case of error deactivate the actor and rethrow the exception

catch (Throwable t) { on.set(0); throw t; }

}

}

In order to be schedulable, the actor must be a Runnable, so here is the run() method:

public void run() {

try {

// if it is active

if (on.get() == 1)

behavior =

behavior.apply(mbox.poll()) // apply the behavior to the top of the mailbox

.apply(behavior); // as a result an Effect is returned:

// apply it to the current behavior

// it returns the next behavior (which overwrites the old in the assignment)

} finally { on.set(0); async(); } // deactivate and resume if necessary

}

Wrapping Up 🔗

In this long blog post we introduced actors as a running example to showcase some of the best features of Java 17. One major feature has been left out, though; sealed type hierarchies.

If you recall, in Behaviors and Effects we noticed that we could

use a specific type of message instead of Object:

interface Message {}

interface Behavior {

Effect receive(Message message);

}

But that would make our entire actor runtime tied to a built-in type of message. Not a huge deal, but still a limitation.

Later, in the Ping Pong Example we mentioned that we had

to always handle the default case because the signature of tell() is:

interface Address { Address tell(Object msg); }

That would not be much better if the signature were:

interface Address { Address tell(Message msg); }

For now, this was the best we could do. However, even Akka now has evolved and it implements Typed Actors. of an actor is actually typed, allowing us to match against sealed hierarchies of types. In Typed Actors, the Behavior and the Address of an actor are typed; i.e., they specify the type of objects that they accept.

This allows you to match against sealed hierarchies of types, and even avoid pattern matching entirely in some cases.

Next time, we will see how to write a tiny chat server with its corresponding client, and run it through JBang; but in the final post, I will publish a follow-up to this blog post with an updated, typed version of this tiny actor runtime, where, instead of:

interface Behavior extends Function<Object, Effect> {}

interface Effect extends Function<Behavior, Behavior> {}

interface Address { Address tell(Object msg); }

we will have:

interface Behavior<T> extends Function<T, Effect<T>> {}

interface Effect<T> extends Function<Behavior<T>, Behavior<T>> {}

interface Address<T> { Address<T> tell(T msg); }

and we will learn what changes will be needed to adjust for that change. In the meantime, you can try it for yourself!

Acknowledgements 🔗

- Viktor Klang published the original snippet and reviewed a draft of this post

- Max Andersen is the author of JBang and reviewed a draft of this post

- I thook some inspiration from Bob Nystrom’s Crafting Interpreters for the writing style of this tutorial

- Miran Lipovaca for the title of his Haskell book